One of the great American poets of my generation has passed. Those of us who came of age in the Sixties had a poetry hero in Robert Bly. By the time I was writing poetry in the San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury, I'd found the Sixties lit mag of translations that had begun in the Fifties. And I was hooked. Leaping poetry. Itki made so much sense!

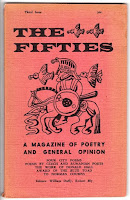

Then I went back and found old copies of The Fifties. I began to realize there was a vast world of poetry beyond our borders. I had come from a seven-year seminary indoctrination. Thankfully, Brother Antoninus (William Everson) had led me into the sphere of influence of the San Francisco Renaissance poets: Kenneth Rexroth, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Lew Welch, Lenore Kandel, Gary Snyder and later Jack Spicer -- to name the most prominent in my personal pantheon.

Snyder and Welch led me to the Beats -- Ginsberg, Kerouac, DiPrima. I was intrigued by Ginsberg performances. Loving his anti-war stance and incandescent presence. Kerouac in his poetry was a wild reservoir of jumping jive language. I was put off by DiPrima, though, who rolled her window up on Market St. when I tried to introduce myself, and I couldn't understand her poem in a Playboy knock-off, urging everyone to fill their bathtubs because the revolution was coming. There seemed to be a bit of the unexamined, self-destructive, self-inflated egotism among some of the Beats that rubbed my woo-woo skin the wrong way.

Bly introduced me to a very different style. I devoured

Silence in a Snowy Field in the early Sixties. His deep image technique intrigued. That led me back to Pound and Williams and then George Oppen, who I had the good fortune to meet on Mt. Tamalpais. We became friends. His Imagist books made deep sense to me and imagery became central to my work. When Bly came out with

The Light Around the Body with poems railing against the Vietnam War, I was on board. That the work won the National Book Award only cemented my admiration.

I fell completely in love with Bly's Tomas Tranströmer translations in 20 Poems. I carried that dog-eared chappie around everywhere. At an anti-nuclear conference in Chicago, I got to see him perform before students at Northwestern University. He used a dulcimer to accompany a poem or two -- endearing him to me as I was a closet aficionado of the dulcimer as well. And he demonstrated how simple hand movements accompanying a poem made for much more entrancing performance chops than merely reading the words on the page. Bly's brilliance had seeped into every pore of my lyric sensibilities -- opening distant worlds of poetry, teaching me to let poetry leap not just ride a set rhythm, exposing me to deep images and poems of political activism that were more than mere cant.

Finally, in the start of the Seventies Ferlinghetti's City Lights brought out

The Teeth Mother Naked At Last, and itki blew my frigging head off. Here was a compendium of counter-cultural tropes I'd been embracing after years sequestered in the locked medieval tabernacle of a seminary. And itki was beautiful poetry, dazzling images, cultural anthropology. Christianity, America's democratic facade, the war that powered the economy -- everything lay exposed. "...the mad beast covered with European hair rushes / through the mesa bushes in Mendocino county..." and "...Let us drive cars / up / the light beams / to the stars..."

I wasn't so taken with Iron John. Itki was important. But I had already embraced feminism by the time itki came out, and his trying to heal the wounded father in his life, in the life of so many men, while needed for the culture at large, wasn't what had me in itki's grip. But Bly's poetry and his earlier publications had taught me so much, I still held him in great reverence. As life would have itki, my dear friend and brilliant poet Judyth Hill of New Mexico and now Colorado, had the wondrous fortune to actually study with him, to have him as mentor and friend. She has given me permission to share this marvelous poem of hers in praise of one of America's greatest poets of our times.

Photo by Bruce Bisping of the Star Tribune

Ghazel Overheard

for Robert Bly

Ache of morning without you, ache

of the book I open seeking you, ache

of absence, ache of voice in my closest listening.

Snow falls in the fields of many grasses

where this October the fox hid, voyeur of pond.

Writing poems, you said, the same: a wild listening.

Odin slung from the Tree, Inanna, stripped of crown, jewels, dominion.

Falstaff and midnight's chimes, Jesu, Jesu, the green green of Ireland,

every loss and landscape play the music of listening.

Cezanne stood in one place, Mont Sainte-Chapelle in another,

connected by the portolan of seeing. We wrote every poem

because you were listening.

The elk herd is here today, wearing thick winter fur,

the small ones near their mothers. Nuthatches, chickadees,

flicker's flash of underwing orange, choral listening.

I only know to leave by losing everything.

I have a house, then I don't: words on the page, then

nothing. Do you hear me listening?

When the plaster cracked revealing the Golden Buddha,

we sat sesshin exactly the same as the day before.

This is our practice, over and over. We are listening.

Wagonload of hay, boxwood, Tranströmer, Antonio

Machado, Rilke. You left us so many gifts. I kept

your Giant mask, the beanstalk still (g)listening.

Yeats wrote Lake Isle of Innisfree on a London bus,

that's the secret, isn't it? Longing eclipses the distance from home to here,

you to us, poem to page. You just keep listening.

JUDYTH HILL